The Western Ghats of southwestern India and the highlands of southwestern Sri Lanka, separated by 400 kilometers, are strikingly similar in their geology, climate and evolutionary history. Together, they form one of the most densely populated of 36 global biodiversity hotspots: biogeographic regions characterized by exceptionally high levels of biodiversity and endemism, as well as significant habitat loss. Seen here in India’s Sahyadris: impatiens acaulis or rock balsam, a species of flowering plant endemic to most of India and Sri Lanka. Photo: Dinesh Valke.

Roots Across the Sea: Shared Ecologies in the Western Ghats and Sri Lanka

Arriving in Lanka was a moment of familiar unfamiliarity. In a move I had not anticipated, I took on a job as part-gardener, part-ecologist at a 19-acre tropical garden on the island’s south-west coast. Despite hailing from a Chikmagalur coffee-farming family and having spent several summers in the dappled shade and towering undergrowth of plantations, I arrived expecting to encounter a largely unknown flora. Instead, I was met with a mix of many floras! Some plants were well-known, others felt like distant cousins or friends from back home, and still others were complete strangers in a strange land. This was, perhaps, not surprising: in the back of my mind I knew that the Western Ghats and Sri Lanka shared ancient continental kinship, but the specific expressions of this relation were far from obvious. Over several months, guided by the garden, I began to see patterns in the plants around me.

Walking through the garden each morning, I came across familiar flowers like bleeding-hearts (Clerodendrum sp.) and blue ironwoods (Memecylon sp.) growing under the dark, unfamiliar canopy of towering tropical rainforest trees like Dipterocarpus sp., Horsfieldia sp., and Humboldtia sp. Familiar fragrances drifted in the still tropical air from flowers which, upon closer inspection, proved to be entirely different from the species I knew and loved.

One of the best-known twentieth century Asian gardens, Lunuganga has showcased a diverse range of flora since renowned architect Geoffrey Bawa transformed the grounds of an abandoned rubber estate 76 years ago. Over 300 species of plants thrive here, overseen by a dedicated team which includes the author, Curator of Living Collections at the Geoffrey Bawa and Lunuganga trusts. Seen here: some of the scenic panoramas contained within its 19 acres (1-3). Photos: Soham Kacker.

The cherished sweet fragrance of coffee flowers, I discovered, came from a species of wild coffee, Coffea travancorensis, native to the Western Ghats. The unmistakable astringent-zesty fragrance of mangoes came not from the familiar low-branching Mangifera indica, but from the towering, round-leaved Mangifera zeylanica—the Sri Lankan wild mango. The basmati-like earthiness of mahua came from the rare Madhuca fulva—endemic to Sri Lanka— which had the same fragrance but none of the succulent petals of its Central Indian counterparts. The fragrant spikes of shell gingers (Alpinia sp.)—garden plants from the coffee estate I had expected to be colonial introductions—turned out to be indigenous!

Mangifera zeylanica, the Sri Lankan wild mango, is a majestic tree that has been marked as vulnerable, according to the IUCN Red List. Scattered across the moist and dry lowland regions of Sri Lanka, it is endangered by logging. Photo: Nyanatusita.

What I assumed to be a dark grove of ebonies (Diospyros ebenum) revealed itself to be half a dozen species of that genus—none familiar, but all producing the same, slightly sour-astringent tasting fruits I remembered from climbing ebony trees back home, as a young boy. Graceful chains of Cymbidium or boat orchids dangled from trees, much like the ones I remembered from the coffee estate, but these bore no fragrance.

At every turn in the garden, memories of my summers in Chikmagalur provided clues to my current surroundings. The ecology of Sri Lanka was written in a script I could read, but in a language that felt foreign. Why did these forests feel so familiar, even though they were different? How had this strange chimaera-like flora come to be? Would that haunting familiarity also extend to how people lived in, around, and with these forests?

Some of Sri Lanka’s flora is reminiscent of cousins in India, while slightly different; some is altogether new. Humboldtia laurifolia, known as gal karanda in Sri Lanka, or little Amherstia tree offers a fresh bounty (1); Madhuca fulva, also known as wana mee in Sri Lanka, has a similar fragrance in India and Sri Lanka, but it lacks the succulent petals of central Indian counterparts (2); Cymbidium aloifolium, the aloe-leafed species of boat orchid seen here gracefully balanced off a tree (3), lacks the fragrance of its cousins in India’s Western Ghats. Photos: Soham Kacker.

Armed with three volumes of The Illustrated Field Guide to the Flowers of Sri Lanka and beginner’s luck, I set out to make sense of this tangled thicket of unknowns. Soon, I found myself wading deep into time.

Understanding Sri Lanka’s present-day flora required an inquiry into its botanical past, and by extension, its geological history dating back 132 million years to when the island was still part of Gondwana, tucked between India and Antarctica. Some Sri Lankan flora traces directly to Gondwanan origins, explaining how some taxa are common across Africa, India, Sri Lanka, South East Asia, and even South America.

Satinwood (Chloroxylon swietenia), for example, is found only in Madagascar, Sri Lanka, and the dry zones of South India—suggesting that it originated when these three landmasses were tectonically close and dinosaurs roamed the shared continent. Other species, like the diminutive orchid Angraecum zeylanicum, found only in Lanka and the Seychelles, or the hanging cactus Rhipsalis baccifera subsp. Mauritania, restricted to Africa, Lanka and the Mascarene Islands, likely dispersed over vast distances to the island back when it was closer to Africa. Some groups, like the huge rainforest trees still present a scientific mystery: their seeds are too heavy for wind dispersal, and they perish in saltwater, yet, they scattered across erstwhile Gondwana and are found today in the Mascarenes, Sri Lanka and Southeast Asia.

The Ceylon satinwood or East Indian satinwood is a tropical hardwood, the sole species in the genus Chloroxylon. Native to southern India, Sri Lanka, and Madagascar, it is seen here in Ragihalli State Forest in one of the Western Ghats’ expanses in Karnataka. Photo: Forestowlet.

A shared Gondwanan origin may explain the similarities between Sri Lankan and South Indian flora, but it is not the complete story. Around 120 million years ago (mya), India split from Gondwana and began drifting northward across the Tethys Sea. Around halfway through its journey, the Indian plate experienced a huge upsurge in volcanism known as Deccan volcanism. This period, which coincided with the extinction of the dinosaurs around 66 mya, lasted over a million years and wiped out much of India’s plant and animal life. Only a handful of mostly aquatic or riparian species survived.

However, the story changed dramatically around 50 mya, when India collided with Asia. This tectonic event created new land bridges for species to migrate into the subcontinent. At the time, both southern India and Sri Lanka lay along the equator, their hot and humid tropical climate encouraging plant life to flourish. Between 30 and 6 mya, a ‘golden age’ of migration unfolded where plants flowed in from East Asia and Africa (which joined with the Asian plate around 25 mya) to Central Asia, then down to India and onwards to Sri Lanka. Since the climate in South India and Sri Lanka was similar and stable, their floras devolved in parallel.

This shared botanical heritage is evident in the beautiful flowers of the blue ironwood (Memecylon sp.), the sweet-smelling punnaga (Calophyllum sp.), and even Sri Lanka’s national tree, the Ceylon ironwood (Mesua ferrea)—all of which grow in the Western Ghats as well as the wet zone of Sri Lanka. However, even among this shared flora, evolution took its own course on the island. Many underwent speciation in Sri Lanka to give rise to endemic species which never made it back to the mainland. The many species of sapphire-berries (Symplocos sp.) are an example: while some species remain common to both regions, the ones on the island radiated into several endemic species.

The Ceylon ironwood (mesua ferrea) is Sri Lanka’s national tree–and it is also witnessed in the Western Ghats. This slow-growing tree is named for the heaviness and hardness of its timber, and widely cultivated as an ornamental for its graceful shape, grayish-green foliage, and large, fragrant white flowers. Photos: Wee Hong (1), Margaret Donald (2).

Around 6 mya, as the Indian plate drifted farther north from the equator, the climate became drier. Aridity replaced the humidity, reshaping the tropical forests of southern India and northern Sri Lanka. Forests thinned and species vanished. The deepening of the Palk Strait severed the land bridge that once connected the two regions, halting plant and animal migrations, and slowly, the two regional floras drifted apart to become more distinct. A common ancestry remained, traced through the vestigial resemblances of the plants only found between the wetter folds of the Western Ghats and the tropical south-west coastal region in Lanka. Pitcher plants, for instance, now grow only in the far south-west of Lanka and in the northeastern rainforests of India, having vanished even from the tropical Western Ghats. Others, like the understory shrub Gaertnera sp. and the towering rainforest tree Horsfieldia sp., once found on both sides of the Palk Strait, have disappeared altogether from the Indian subcontinent.

The pitcher plant–Nepenthes distillatoria, endemic to Sri Lanka–is an insectivorous plant, producing pitcher-like traps at the ends of its leaves into which insects fall and are digested in the fluid at the bottom of the pitcher. No longer found in the Western Ghats, it has a cousin in Nepenthes khasiana, found chiefly in Meghalaya. Botanical illustration: Joseph Paxton (1). Photo: James & Jana Hans (2).

Higher elevations were spared the increasing aridity, with their cooler, moister, and more stable climate making them islands of continuity. To this day, the Nilgiris in India and the Central Highlands of Sri Lanka echo their botanical kinship—remnants of a shared past.

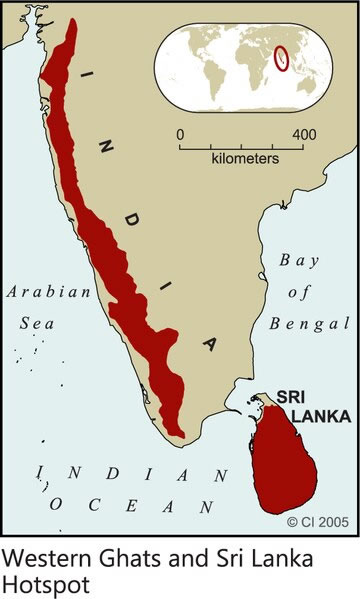

A vital hotspot: the Western Ghats in India, marked in red, and the span of much of Sri Lanka, also in red, identifies the span of this biodiversity hotspot. The breakup of Gondwanaland is one of the factors that shaped the geological history of the region (map courtesy Conservation International), whose southwestern forests are seen in this image (2). Photo: Soham Kacker.

So why did Lanka’s forests feel familiar? In part, it was the ancient continental sisterhood of lands cleaved from the same landmass—two parted shores sharing a lost tropical bond. It was also due to the shared human past of the two countries; for it was the people who continued to carry plants across the waters. Indeed, plants like the ubiquitous kithul palm (Caryota urens), now central to Sri Lanka’s botanical identity as a source of local palm toddy and fine jaggery, are thought to have been brought to the island by early humans. Trade and the Age of Exploration brought in others like the temple trees—frangipani or araliya (Plumeria sp.)—which were introduced in the 16th century from Mexico through the Spanish occupation of the Philippines. These trees became an emblem of Colonial ‘tropical’ aesthetics, but its flowers also became a beloved local offering at temples. The Dutch and British later introduced plantation crops like coffee and tea, ornamental plants like the gulmohar, copper pod, Tabebuia sp., and the jacaranda—all adored even in Indian cities today.

Perhaps, a deeper familiarity also came from the similar ways in which people knew the flora—many had an intuitive ease of navigating and interacting with plants. Conversations with my fellow gardeners revealed their deep knowledge—of the plants’ common uses, medicinal properties, mythological associations, seasonality and superstitions—that extended beyond taxonomy and biogeographical origins. Answering my curiosity about a handsome young sapling, the priest at a village temple told me the story of how the śāla (Shorea robusta) was the sacred tree under which the Buddha was born, and to this day blooms around Vesak, the sacred festival of the Buddha’s birth, enlightenment, and death. When I asked about a dark-leaved tree in the garden, a gardener who also happened to be a skilled carpenter, introduced me to the kalu mediriya (Diospyros quaesita), with a prized heartwood that could only be used for the most precious carvings. A knowledgeable elderly gardener pointed out the vining tendrils of the medically important ōlin̆da-vael (Abrus precatorius), which could treat skin ailments and kapha dośa, and its seeds could be used as jeweller’s weights to measure gold, just as they are in India.

A herbaceous flowering plant from the bean family Fabaceae, Abrus precatorious is a slender, perennial climber with long, pinnate-leafleted leaves that twines around trees, shrubs, and hedges. It has well-known medicinal uses, including the treatment of skin ailments, in both Sri Lanka and India. Photo: Soham Kacker.

As I had done in India, here too, I found a way of knowing which was not just cerebral, but sensory. To know the plant was to interact closely and intimately—to touch, to taste, to inhale. No field guide could teach what the body could learn through its own slow attentiveness. The gardeners introduced me to the iconic Lankan cinnamon (Cinnamomum zeylanica) not by name, but by taste—showing me how to peel away the outer bark from a branch to taste its inner pith. I learnt about the rata-gōraka (Garcinia xanthochymus) the same way—by prising apart the small, soft fruit and tasting its yellow flesh, its floral and sweet flavour immediately revealing its relation to the mangosteen. I learnt the ankenda (Acronychia pedunculata) through scent—an oily-citrusy fragrance which lingered on your fingertips after crushing the leaves. Like its cousins in the citrus family, it offered itself as medicine—a tincture for scrapes, bruises and small abrasions.

Across India and Lanka, intuitive and multisensory ways of knowing are woven into shared languages, rituals and narratives. The ancient Mahāvaṃsa tells of the arrival of the Bodhi Tree (sacred fig) from India—how it sailed down the Ganga from Pataliputra, skirting the east coast of India before being ceremoniously received in Sri Lanka. Much like the Arthaśāstra, the Mahāvaṃsa states planting trees as one of the principal duties of kingship. Such texts trace common sensibilities relating to the botanical landscape. A Sinhala folk tale about a man who dreams of planting kithul seeds and becoming wealthy from the jaggery mirrors the Panchatantra tale of a man who dreams of acquiring similar wealth by selling a pot of grain.

Both geographies also share a common spiritual imagination which envelopes even foreign species. In the large and sweet-smelling flowers of the cannonball tree, introduced in the 15th century and now worshipped on both sides of the Palk Strait, Sri Lankan Buddhists see a stupa, while Indian Hindus see a Shiva lingam. Pachchaperumal, a landrace (a living, local, domesticated variety that has evolved over time) of rice whose name refers to the golden hue of Viśnu, now grows abundantly in the Jaffna region of Lanka; but its name has been reinterpreted locally to refer to the golden colour of the Buddha, for local legend says it came to the island by accident, tucked within the folds of His robe.

Biogeographical histories and shared taxonomies may not be visible or self-evident in the world around us. They live quietly in the ways people speak of plants, and gather, taste and know them. Over generations, these deep-time movements—of landmasses drifting, forests shrinking, species crossing and parting ways—become folded into local knowledge systems, recipes, rituals and remedies. Our cultural memory bears traces of these deep-time movements and continues to evolve alongside them. Perhaps, this common knowledge is why this landscape felt familiar despite being so different; for, while the vocabulary may be different, the grammar is the same.

Correction: An earlier version of the article stated that Nepenthes mirabilis was found in the Southern Western Ghats of India, and featured an image of the same. Nepenthes mirabilis does not, in fact, grow in the Western Ghats.

*Further reading: the author consulted and suggests readers consult the following texts: The Mahavamsa or The Great Chronicle of Ceylon by MH Bode and W Geiger; ‘Biogeography of Sri Lanka’, Ceylon Journal of Science by N Gunatilleke 46 (5), 1; ‘Biogeographic affinities of the Sri Lankan flora’, the doctoral dissertation of LD Kumarage (2025); Village folk-tales of Ceylon (Vols 1-3) by H Parker; The Ecology and Biogeography of Sri Lanka: A Context for Freshwater Fishes by R Pethiyagoda and H Sudasinghe; and Kautilya’s Arthasastra by R Shamasastry.